In the course of preparing a post that features my 2009 interview with Lawrence King, I was shocked and saddened to learn that Larry passed away over three years ago, on March 14, 2017. If you're reading this, you already know that Larry was the gifted, inventive and extraordinarily powerful sticksman for Wimple Winch and Pacific Drift.

He was also one of my personal drumming heroes.

I suppose there is no greater tribute for him than to post my interview with him, as planned.

Note: The following introduction was written prior to learning of Larry's passing. Sadly, my discovery occurred while investigating the possibility of doing a followup interview with him.

After an extended and regrettable hiatus, I am delighted to say I’m back with a long-overdue resumption of my celebration of Freakbeat legends Wimple Winch (going forward, I'm planning a series of in-depth, song-by-song posts, similar to the approach taken on my other blog, The Clarkophile). Today's post is a newly edited publication of a 2009 interview I conducted with Lawrence King. Lawrence has always been a drumming hero of mine; his deft (I said deft, not daft, Barrie!) blend of power and precision, both in the Mighty Winch and Pacific Drift has captivated me for years. Why is it only appearing here now? Fair question. As you may or may not know, I wrote a feature piece for Shindig! back in 2009. I had originally planned to include interviews with all four members—Dee Christopholus, Lawrence King, John Kelman and Barrie Ashall—but was not able to make that happen. In the end, only Dee was quoted in the piece, and so I thought this blog might be a means of providing additional information.

Full disclosure: the following interview has been published elsewhere (with my full blessing!) but for reasons of posterity and readability, I wanted to repost it to this blog.

Q. Are you a completely self-taught drummer? Who were your drumming influences?

Lawrence King: Yes, I am self-taught, if that's the right word. I guess just listening to guys like Buddy Rich and Joe Morello on the early records I got my hands on gave me the ideas of what was possible, although I didn't know how it was done, so I tried to figure it out for myself by listening to their recordings and practising as much as possible.

At the outset of early Elvis, Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, Carl Perkins et al, it was about reproducing what I was listening to, which was the way we, as a band gathered a set of numbers we could do at gigs. Most of our early stuff were covers so all those drummers on the records I listened to were my teachers. Incidentally, I did 1 gig with the Silhouettes with just a snare drum and hi-hat! [This was] due to having to save money to acquire additional pieces which I did over a few months, which eventually led to a full Premier kit.

At the outset of early Elvis, Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, Carl Perkins et al, it was about reproducing what I was listening to, which was the way we, as a band gathered a set of numbers we could do at gigs. Most of our early stuff were covers so all those drummers on the records I listened to were my teachers. Incidentally, I did 1 gig with the Silhouettes with just a snare drum and hi-hat! [This was] due to having to save money to acquire additional pieces which I did over a few months, which eventually led to a full Premier kit.

I went to see [Joe] Morello at Liverpool's Philharmonic Hall when Dave Brubeck played there and was agog at his technique. I bought myself a drum music book but could never get my head around the written notes and relented, allowing my busking ear to sustain me. Little did I realize at the time I would play at the Phil myself some years later when, as 4 Just Men we came fourth in a 'Battle of the Bands' contest out of over a 100 entries and I won the "most promising drummer" award presented by George Harrison, of all people!

Later on, my influences were contemporaries like Keith Moon, Ginger Baker and Mitch Mitchell, although I was always trying to create my own style and sound. (Drum tuning became very important to me later on especially for those rolls that incorporated using my full kit and the sound that different size cymbals made when hit at varying strengths and angles.) Later on when using a Ludwig kit and Zildjian/Paiste cymbals I got close to that overall sound and feel I had been looking for.

|

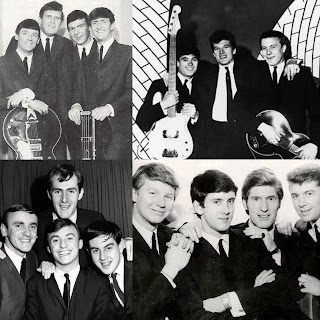

| Clockwise from top left: The Fourmost; The Big Three; The Searchers; Gerry and the Pacemakers |

Q. Your early Merseybeat period featured many personnel changes. Was this typical of the Liverpool scene? Was there a high attrition rate as you separated those who were serious players from those who saw it as a hobby?

In our case, changes were made more due to circumstances than a plan of some kind. For instance, Pete Turner had dependent family and couldn't easily turn fully professional when we decided to, after the BOTB gig. John left a few days before this competition to join Freddie Starr's band and we had to quickly find a replacement, which we did with Lal Stott—although we knew at the time his tenure would be brief due to his other commitments. I think we would have come close to winning the contest had John not left so suddenly. Other bands around did make changes (The Beatles were the most famous example) but I didn't notice whether or not this was typical of everyone; for instance, Gerry & the Pacemakers, The Searchers, The Big Three, and The Fourmost all seemed settled when the scene went national. However, I guess that a lot of bands did, as everyone began jockeying for position when the talent scouts swarmed all over the city.

Q. You and Dee were the only constants in the band over its history, from beginning till end. I'm aware that neither of you got to meet your respective fathers because they were lost at sea. To what extent, either consciously or subconsciously, do you feel this created a bond between the two of you?

LK: It was something we occasionally discussed but not a great deal as we had been friends since childhood. I think there was a bond between us but rather more subconsciously than otherwise. I think we both shared a common vision in those days that we could contribute musically to the scene with something unique, as we were always trying different things to improve our set list and stage act—a lot of which were downright daft and failed miserably.

For instance, we started one gig all laying on the floor when the curtains opened but when we stood up Harry inadvertently pulled out his bass lead and Dee's microphone never worked—a complete shambles! However, we did have our differences, which sometimes became pretty heated, but we always put the welfare of the group before any personal bickering and were usually able to resolve issues this way without too many compromises.

Incidentally, my own father probably died in hospital in Nova Scotia after being rescued and could be buried in Canada somewhere although I have no way of confirming this. However there's no doubt this bond helped us through some hard times.

Dee and I were firm childhood friends and shared a lot of our formative years together, which briefly stopped when his family moved out of the area. But they soon resumed and I recall when he came to me with Elvis's ‘Jailhouse Rock’ that he was entering a talent contest and wondered if I could learn the drum riff in it—which I did but to no avail as the resident 12-piece band at the Grafton wouldn't let me sit in on the drums to accompany him. But to his credit he won the heat without my assistance but it was the first instance of our collaborations together.

You also have to appreciate the environment we grew up in, the aftermath of a World War, the shortages and lack of basics that were around for kids during the '40s and early '50s. Music was an escape, especially the early R&R records that were coming over from the States, and offered us a new an exciting world to explore.

Q. John Kelman's guitar playing strikes me as having been rather eloquent for the period.

Can you give me a brief assessment of his style from your perspective?

LK: When we first met John he had a red Strat(ocaster), a Vox amp and an echo chamber and seemed very much influenced by Hank Marvin. However, he was technically excellent and had a really good busking ear and could work out the chords on a record by listening to it a few times —which was a great asset as we did quite a few covers in those days.

When he rejoined us after his Freddie Starr experience, and just prior to our auditioning for Decca and Parlophone, his style had changed and had become more specific and gutsy. Despite having been really annoyed at his original defection he soon won me over with his 110% effort and original guitar riffs which definitely added to the band's sound. He used to invent some interesting riffs and his solos were as inventive as they could be given the structure of each song. His overall sound got more varied too as he acquired additional pedals and gizmos that were available at the time. (There were times in Germany when he came off stage with his fingers bleeding profusely from splits caused by the heavy workload.)

Q. And how about Barrie (Ashall)?

LK: Barry was the best bassist I ever played with (although Graham Harrop in Pacific Drift was good in his own way). His style of playing was totally powerhouse and he looked and played like Mark King (Level 42)—only years before he ever emerged. There were times in Germany where he completed a set with just two strings and we hardly noticed.

His fingers were like lightening up and down his guitar fret covering the notes. His live performances were something to behold at times and I consider him instrumental in the sound we achieved and a great asset. He too never held back and gave 110% in his playing. We developed a great understanding musically onstage and the bands tightness started with him and me.

"In retrospect, I feel Wimple Winch developed more as a direct result of the way Barrie and myself developed a greater understanding of each other's styles and began to play off each other accordingly."

Q. The band's heavy guitar period, later dubbed "Freakbeat" by Phil Smee, was a dramatic change from the earlier tracks. Your drumming also came more to the forefront. How did these changes creep into the band's consciousness? What were you all listening to during this '66 period?

LK: In retrospect, I feel Wimple Winch developed more as a direct result of the way Barrie and myself developed a greater understanding of each other's styles and began to play off each other accordingly. This, in turn, drew in both John and Dee. There were times when I felt we were somehow 'competing' with each other, if that's the right term, for dominance. But somehow we knew when enough was enough and never really tried to outdo each other too much, as there was an understanding when things looked like [they might be] getting out of hand and the band's overall performance looked like it might suffer.

We used to improvise and experiment on stage, especially when some songs got extended to fill some of the time slots we were playing in Germany when five appearances of 40 mins each night were the order of the day. We introduced a solo for each of us to extend certain songs and for me the drum solo was something I really enjoyed. As for listening to other bands I suppose the likes of The Beatles, Spencer Davis, The Kinks and The Rolling Stones were getting the airplay on the radio along with more and more of the American responses like The Byrds, The Doors and Frank Zappa which we sometimes heard when travelling in the van. But in my mind it was when we supported Jimi Hendrix at the 'Ship' that I think we woke up to what was happening, and a much more aggressive approach to our music seemed the way to go, and volume, feedback, and raucousness crept into our sound.

Q. How many tours in all did the band undertake? Acts like the Who were far better on stage than in the recording studio. Was this the case with Wimple Winch? Imagine there is an extant, pristine recording of a typical WW gig from '66/'67, in your mind how would it stack up against the studio recordings?

LK: I lost count of the gigs we undertook but it was considerable and when appearing as Just Four Men we sometimes did three gigs a night in and around the Manchester and Merseyside area. The major tour with Del Shannon, Hermans Hermits and Wayne Fontana took us all over the UK in the space of just over a month. A shorter tour with The Rolling Stones lasted about two or three weeks. Then we were in Paris for six-eight weeks on our own and another time we were there was backing David Garrick but I'm not sure if this was before or after. Then we went to Germany and were away from home about two months, maybe longer.

As for live versus studio, the disciplines are different but there was more freedom live to try new things and let loose when playing, although the acoustics of different venues meant you weren't always sure how the overall sound came off the stage. And of course in those days setting up for a gig—sometimes without the help of a roadie after driving miles in the van—affected us also. It was only when recording and they miked up each instrument and used maybe three or four mikes on the drums that we became painfully aware that a more powerful PA system was required. Then there was how mistakes showed up starkly in a studio but could be overlooked onstage. But to be brief, I think the gigs I would have loved to record were the ones we did in Redcar with Free but foremost by and a mile was the Hendrix gig [February 12, 1967]. The [Sinking] Ship was an old wine cellar, very much reminiscent of the Cavern and had great acoustics and atmosphere. For different reasons these were the ones that came closest to our studio sound we had at the time, at least in my mind.

|

| Jimi Hendrix Experience at the Sinking Ship, February 12, 1967; support act Wimple Winch |

For more on the Hendrix gig, click here.

Q. You are credited as co-writer on a number of tracks. Can you briefly describe the nature of your contributions?

LK: My songwriting contributions were limited to lyrics and sometimes suggesting an arrangement or chorus insertion, but by and large it was mainly Dee and John. (I later developed more writing skills with Pacific Drift working alongside Barry Reynolds.)

"I still reflect on what we could have done had we had a few more decent breaks and a recording company prepared to stick with us"

Q. Are you surprised that WW has retained a cult following over forty years after its final recordings were made? What, in your opinion, is the band's best track?

LK: Yes, I am surprised with the legs those recordings have. It's a pity that two additional tracks from the Fontana sessions were lost. [There was] one called 'Invisible Man' and 'Hoo Whaa, Hee' which I rather liked. I also like 'Things Will Never Be the Same,' a flipside of 'That’s My Baby,' as it was as close to our Merseybeat influences we had in those days. But I suppose 'Save My Soul' closely followed by 'Atmospheres' and 'Rumble' are the best.

Wimple Winch — 'Rumble on Mersey Square South' (1967)

Q. After the fire at the Sinking Ship, did you have the sense that this was the event which spelled the band's end? Did the band just peter out gradually?

LK: The fire at the Ship was a watershed inasmuch that a lot of gear was lost and the insurance Mike (owner/manager Mike Carr) had on the club apparently never covered our instruments. And with our funds being depleted, replacing what was ruined became very difficult. Also I think we felt that an era had passed and that without a recording company or decent agent our options were limited.

I remember talking to Dee in a Stockport cafe about an offer I had received to join another group (which later turned out to be Pacific Drift) and agreeing that WW had little prospect of re-igniting and that there were new roads to travel. But it was a wrench for sure as WW had become my whole life and probably theirs, too. So I finally moved on to pastures new.

In a way it turned out that I had success with the Drift and had a great time with a group of great musicians. forging another bond and creating some great tracks and taking my drumming to another level. I still reflect on what we could have done had we had a few more decent breaks and a recording company prepared to stick with us. Ironically, when Bam Caruso re-issued some of the recordings in 1986 three of us seriously considered reforming, but without Dee it would have been rather pointless.

Pacific Drift — Feelin' Free (1970)

Q. I am quite fond of the May '68 demos. Most people I know refer to them as "whimsical", but to me there's an undercurrent of wistful melancholia to them. I also believe they show the band at the height of their powers as writers and musicians.

Can you provide brief thoughts on these songs?

LK: If I'm not mistaken, after raving about the Pet Sounds album, Dee had written some new songs which we recorded at Neil & Hardy's studio in Stockport with a view to lining up some further releases with Fontana, which they regretfully declined. I think we were on the verge of entering a new phase musically with ideas on a different level to what we had done before. As I recall these songs would have been the springboard to a much more adventurous creative stage which, in effect, was killed at birth by the Fontana hierarchy.

The wistful melancholy you speak of probably reflects the way we were feeling at the time, especially with the lack of recognition nationally after the release of the three Wimple Winch singles.

Lawrence "Larry" King (Arendes)

August 18, 1941 — March 14, 2017